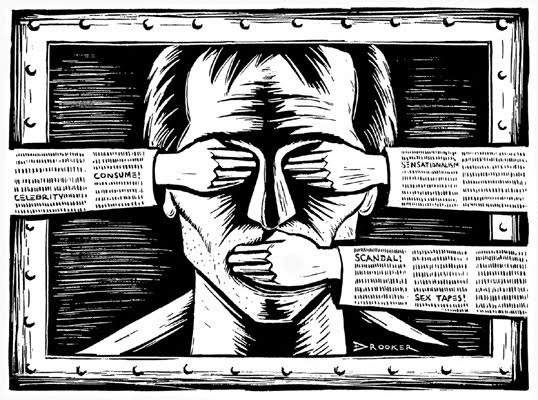

The silence of the lambs

The muffled announcement of PBS’s new CEO, Anton Attard, compounds what is already a problematic situation in terms of freedom of the press in Malta.

The post of PBS CEO is a significant one, and as such the news related to the person given this role should have got the attention it deserved. Instead, PBS buried the news towards the end of its segment last Sunday (August 22).

August is in fact a peculiar time to choose to announce such an important appointment, as it’s usually regarded as the perfect month to bury unpalatable news. This is particularly disturbing when considering that when newspaper Illum reported last January that Anton Attard’s name had been mentioned at Castille in relation to the post, the speculation had been strongly rejected by PBS.

The appointment of PBS’s CEO should be trumpeted from the hilltops. A CEO’s reputation rubs off onto an organisation, which is why corporations usually announce new managerial appointments with pride. Perhaps this is not such a momentous occasion for PBS.

Anton Attard is not a new figure in the public domain – he is the former head of the TV station owned by the party in government, and as such he has a trusted position within the Nationalist Party. This is a bit too close for comfort, especially when Anton Attard joins other party faithful, including Natalino Fenech (Head of News) and Editorial Board chairman Joe Pirotta.

This is not about whether Anton Attard has the necessary credentials for the job. This is about the questionable independence of Malta’s national broadcaster. PBS has a public duty. It is at the service of the public, not the government.

That obligation is not to be taken lightly, especially when considering that the other TV stations with the resources to compete with PBS are mouthpieces for the two political parties. And TV is the main source of news for the majority of the Maltese public.

The point of media liberalisation was to widen the space between civil society and the state, to produce greater diversity of content, perspectives and opportunities for opinion to flourish. In Malta, that space was largely taken up by the political parties to multiply their opportunities for propaganda. In such a situation, the country cannot afford to have the national broadcaster acting as a puppet for the party in government.

You may say this has always been the case. True. But this government promised something different with the ‘restructuring’ of PBS six years ago. We even had a National Broadcasting Policy drawn up in 2004.

It leads with PBS’s mission statement: “PBS serves the general public as well as particular segments of the population by striving to be the most creative, inclusive, professional and trusted broadcaster in Malta”. PBS’s actions related to this announcement are not contributing to its desired reputation as the most trusted broadcaster in Malta.

The situation is not particular to Malta. News making and governing have historically interpenetrated each other. Ever since the emergence of the printing press, which dissolved control of knowledge and interpretation from the clasp of institutions of power at the time and fomented the development of ideological politics, governments have tried to maintain control over channels of communication.

The forms of control have been part of a continuous process of change as the social and political contexts in different societies have changed over time. Yet, any intervention aimed to influence, rather than inform, continues to be a restraint on media freedom. This also applies to privately owned media with a vested interest in driving a particular agenda forward.

The media is supposed to be a network for communicating information and points of view, which eventually transforms them into public opinion. It is what Habermas referred to as ‘the public sphere’ - the part of life in which one is interacting with others and with society at large.

Public opinion in Malta is a sad state of affairs. It is evident in comments following online stories, which reveal a remarkable lack of knowledge of issues. It points to an urgent need for the media in the country to take seriously its duty to inform and educate, rather than just entertain and distract the masses from the real issues that demand scrutiny.

-

.png)

National

PN decries government failure to provide HIV-preventing medicine

-

National

Budget 2026 benefit increases start reaching families and pensioners

-

National

Six rapid response vehicles added to Mater Dei fleet

More in News-

Business News

Joseph Portelli exits CF Estates shareholding in €6.65 million deal

-

Business News

Developer freezes Lidl Malta funds over Żebbuġ site dispute

-

.png)

Business News

HSBC Malta employees to get €30 million in compensation after CrediaBank sale

More in Business-

Other Sports

Pembroke Gymnastics announces successful completion of four-day training camp

-

Motorsports

McLaren Lando Norris wins first F1 world title in dramatic Abu Dhabi finale

-

Motorsports

Three-horse race to the chequered flag: Who will be crowned king in Abu Dhabi?

More in Sports-

Cultural Diary

My essentials: Nickie Sultana’s cultural picks

-

Music

Marco Mengoni stars at Calleja Christmas concert

-

Theatre & Dance

Chucky’s one-person Jack and the Beanstalk panto returns to Spazju Kreattiv

More in Arts-

Opinions

2026: So, it begins!

-

Editorial

Advancing the arts in 2026

-

Opinions

The first domino: Why 2026 is Malta’s moment for a real alternative | Mark Camilleri Gambin

More in Comment-

Restaurants

Gourmet Today festive issue out this Sunday

-

Recipes

Savoury puff pastry Christmas tree

-

Recipes

Stuffed Maltese bread

More in Magazines