Mintoff and I

In our assessment of Dom Mintoff we need to ask ‘why?’ he took certain decisions within the context of his time and how those decisions fitted within his vision.

The news that Dom Mintoff was admitted to hospital reached me via a text message in Dublin. I was listening to a wonderful keynote speech by foreign correspondent Robert Fisk, who delivered a passionate appeal to a group of international journalists. In your effort to explain complex world affairs, keep asking ‘why?’ he said. Indeed, the media often churn out ‘facts’ that are divorced from adequate explanations of the context that caused them.

As soon as I shared Mintoff’s news, one older reporter recalled when in 1973 Mintoff blocked a CSCE agreement in Helsinki until all sides agreed to include a reference to the Mediterranean in the final agreement. For this role, many still admire him. I soon engaged in my own nostalgic reminiscences.

I am fully aware that memory has a strange relationship with history. It tends to blur, it tends to cut corners and is often tinged by emotion. While memory is deemed to be less reliable than documented history both can be equally selective and distorted. What follows is not a clinical account and yet it is worth writing because our life stories empower us to convey our own history.

I was born during the political-religious disputes of the 1960s. Religious sanctions were then imposed on Labour activists and the readers of that party’s newspapers. However my own my baptism was never an issue. I formed part of my extended maternal family that was both very religious and very apolitical.

But nannu Ganni, who lived in another village, was a staunch Mintoff supporter.

His love affair with Mintoff began in the 1950s in an accidental furious exchange between il-Perit and a humble road worker. Mintoff paid an unexpected visit to Mellieha and told the workers they should have been more productive and taken shorter lunch breaks. In a media-scarce environment, nannu and his colleagues did not recognize their Minister of Public Works. Their lack of deference cost them a wage cut that pinched the pocket of a family of eight. But that day, nannu also learnt something about Mintoff’s vision and he became a loyal follower. Nevertheless, nannu Ganni was illiterate and not very articulate. As a result, during the clashes with the church he did not have the credentials to earn himself an interdiction.

My earliest memory of Dom Mintoff is a small monochromatic picture. After the 1971 election, nannu Ganni paid us a rare visit from the other village. I was merely five and yet he presented me with a picture of his idol. Scandalized, my nanna Rozi quickly moved in to destroy it. She gave me instead a holy picture of the Sagra Familja.

Until my adolescence, I identified Mintoff with tal-franka stone. Now this surely necessitates some explanation. Dad first worked in a quarry and later as a stone mason. His working day began at 5am and he never returned before dark. Mintoff became his hero when he reduced the size of the Maltese stone so that its weight became bearable for construction workers. Dad spent his days climbing ladders carrying heavy stones and this decision was a big relief. He is grateful for it to date.

Mum was converted when Mintoff took measures to protect workers’ rights whereby my dad’s contractor had to honour his wage obligations even on those days when heavy rain disrupted their effort. I clearly remember dad’s resentment: “I climbed up and down the ladder for seven or eight hours but the contractor did not pay us anything because rain prevented us from completing the full day’s work”.

When I was young,dad worked long hours and mum tilled the fields but this was hardly enough. We only moved to a house with a bath when I was 6 or 7 and I was about that age when my family acquired their first television set. Even my maternal grandparents finally became Mintoff supporters when he introduced pensions and freed them from their anxieties on how they were going to survive on meagre life savings.

So yes, I was raised in a family that idolised him. It was in my adolescence that I first heard critical voices and I quickly understood there were others who had different experiences. Initially I put it down to class perspectives.

But as I grew older I also felt that he had made mistakes; such as his loss of control over some dangerous Labour exponents. I also noticed that while my own family had made legitimate advancement, some others had acquired questionable advantages. By the time I reached the end of my teenage years I had seen core left-wing principles being breached, the anointment of a successor who was still unable to rein in the loose cannons. I observed a population that had generally improved its standard of living but was becoming restless and frustrated as it was demanding less state control and more market freedom on goods and services that ranged from education to pasta and chocolate.

In this context,I first noted that our environment was being blatantly abused and depleted. Trade-unions were weakened through divisive partisan tactics. I could observe that the move towards gender parity had stalled. Violence by dubious characters was employed before my own eyes to hamper the growth of civil society. This unfolded amid claims of human rights abuses, of corruption and widening tribal political divides. Moreover, I became increasingly uneasy as Maltese media did not merely reflect polarization but they helped to reinforce and widen the divide between the two sides.

At that point, I deleted Mintoff from my mental altar and embraced critical perspectives where I adopted a healthy mistrust of politicians of all hues. Like most of the working-class kids of my generation, I had middle-class ambitions. Then I had exceeded all expectations the day I obtained my O Levels, but I soon realised that further educational capital could open the way for me to reach those aspirations. My parents responded with ambivalence: initially they accepted, but not necessarily understood, my insistence on further studies; they were pained and annoyed about my critical views and so we stopped discussing them.

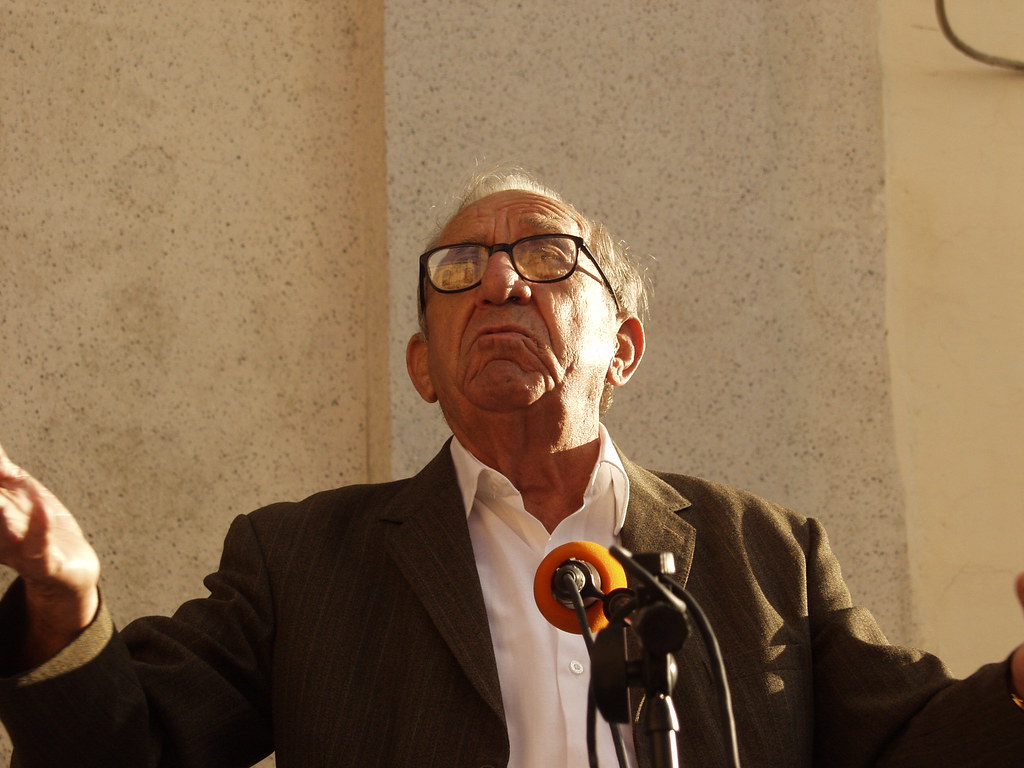

Throughout my life I have heard thousands of Mintoff anecdotes from people who knew him closely. Personally I only encountered him once. It was sometime in 1995. It was a cold autumn evening and I was tired and cold waiting to conduct an interview with an MP. Parliament was in session and I was on my own waiting in the rather bare Opposition room. Mintoff entered and fixed his attention on an old picture that decorated the wall, which showed Manwel Dimech’s memorial in front of Auberge de Castille. He seemed to be thinking aloud. “Those trees are cluttering the space, they are overshadowing Dimech. Mhux sewwa!” He then turned to me and asked if I agreed.. .I suspected he did not really expect an answer.

I was somehow not too surprised with Mintoff’s rejection of Alfred Sant’s style of leadership. For days in the summer of 1998, many of us were stuck to our radio sets listening to his soliloquies. What surprised the old Labour generation like that of my parents, was that he had the nerve to bring down his own government over a project which most people approved of.

Recently I believe it was an article by Noel Grima which speculated that in 1998 Mintoff was bluffing and he was outwitted by Fenech Adami. It is up to historians to confirm whether it is true that Mintoff had assumed the Labour government would not lose the vote. The journalist wrote that John Dalli was away in Libya but on the day of the vital vote, he was flown back on a private jet to cast the vote that led to the end of the Sant-led government.

Irrespective of his intention, Mintoff did bring down his own government. In spite of later PL efforts to rehabilitate and reconcile with him, he did kill Sant’s ambition to inject some new perspectives into our political culture. Sant favoured meritocracy and this sadly stirred more opposition within his own party, than substantive issues like VAT or EU membership.

According to the grapevine, in recent years Mintoff spent more time talking aloud. There were rumours that he was working on his biography but unlike de Marco or Fenech Adami, his account and his interpretation of events have not seen the light of day. It is rumoured that Mintoff was not even eager to disclose his memoirs with historians.

In recent years we have observed that in spite of his deteriorating health conditions, some political figures still found it useful to bask in his shadow. We have also seen some cruel and undignified pictures of a very old and weak man waving his walking stick at intrusive journalists as if to scare them away. We can now even peek at the leaked rambling of his later years.

His hasty rush to hospital reminds us that although there were many occasions were we perceived him to be bigger than life… he is only human. If he goes before I do, I will join others who wish to assess his achievements. Some columnists will always resent him. Others will show a detached respect mainly from a very middle-class perspective.

But let us remember there is an aging and dying generation, like that of my parents, which still feels that his term lifted them up and provided them with a social safety net. In a post-colonial Malta he also inspired many to hope for a better future. In our assessment of Dom Mintoff we also need to ask ‘why?’ he took certain decisions within the context of his time and how those decisions fitted within his vision.

-

National

Robert Abela: No woman will go to prison for abortion on my watch

-

.png)

World

Trump slaps tariffs on European countries in attempt to bully them into giving up Greenland

-

National

Activists urge authorities to ensure access to Fort Tigne remains public

More in News-

Business News

Developer freezes Lidl Malta funds over Żebbuġ site dispute

-

.png)

Business News

HSBC Malta employees to get €30 million in compensation after CrediaBank sale

-

Tech & Gaming

When big budgets stop working: SOFTSWISS shows how ambient marketing reconnects brands with people

More in Business-

Football

Siena Calcio reject €1.3m takeover bid from Joseph Portelli

-

Football

Looking forward 2026 | A World Cup of records

-

Other Sports

Pembroke Gymnastics announces successful completion of four-day training camp

More in Sports-

Cultural Diary

My essentials: Nickie Sultana’s cultural picks

-

Music

Marco Mengoni stars at Calleja Christmas concert

-

Theatre & Dance

Chucky’s one-person Jack and the Beanstalk panto returns to Spazju Kreattiv

More in Arts-

Editorial

Ricky’s whitewashing kangaroo court

-

Opinions

When the road is to blame, file a claim |Shaban Ben Taher

-

Opinions

Gozo’s next confident step forward | Clint Camilleri

More in Comment-

Articles

Planning Authority showcases Malta’s digital future in spatial planning

-

Recipes

Stuffed Maltese bread

-

Projects

Halmann Vella’s stonework in a private residence

More in Magazines